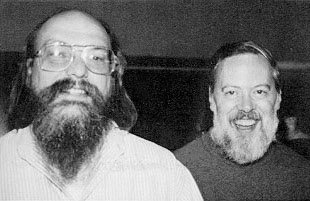

—Who are these people? That's a freaking awesome '70s geek style! My god that hair, those beards… 🤌 😘

—They are Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie, original creators of the Unix operating system.

— 🤣🤣🤣 Nerds! And from the '70s! I knew it! Why are you looking at their photograph?

—I was looking into the Unix Philosophy principles.

—How so?

—The other day I was thinking that Unix is a pretty remarkable thing.

—Why?

—Well, Unix has been around since the ’60s, and together with Linux, which was inspired by it, it now runs around 70% of the world’s servers.

—Yes, I know, and?

—Isn’t it incredible that a piece of software over 60 years old has withstood decades of constant change while staying true to its original design?

—"Good design is long-lasting," as he once said.

—Yes, but have you ever wondered what exactly in its design has made it so resilient?

—Well… not really… Wait! I get it! That's why you were checking the Unix Philosophy, weren't you?

—Exactly.

—Did you find something interesting?

—Sure I did! The Unix Philosophy can be summarized in three principles. They give a lot of insight. Here's the first one:

—Hey, I remember this one!

—Indeed, this one's widely known.

—Pure poetry, isn't it? Software engineering zen.

—Absolutely! It emphasizes the importance of keeping your code focused and avoiding feature creep—something we all strive for but often struggle to achieve. The last two are less well-known but just as relevant.

Here’s the second one:

—This one’s pretty obvious, isn’t it? Feels like a direct consequence of the last one.

—Can you please explain?

—Well, if your programs are going to be highly specialized, they’d better play well together, right? That way, you can combine them to tackle more complex tasks.

—That's exactly right! The more specialized your programs are, the better they should integrate to solve complex problems.

But hold on, there’s still a third one, and this one is particularly intriguing…

—Oh, wow, I hadn't heard about this one!

—This one's less known. What do you think of it?

—It's oddly specific to be a principle, I'd say. It reads more as an implementation requirement for the second principle.

—That's exactly what I thought. I find it fascinating. These two geniuses realized that it’s not just about making programs work together, but about ensuring they do so in the simplest, most straightforward way possible.

—Hmmm… good point. It’s like the easier things are to integrate, the more adaptable the whole system becomes. And now that I think about it, that makes total sense.

—Exactly! The whole set of principles makes for an interesting pattern. Look at this…

—That makes for a pretty adaptable structure.

Picture this as a bowl full of marbles:

—Well, that's a pretty abstract sketch.

—Indeed. I hope it serves its purpose. Now, what would happen if we now move the marbles from a bowl into a box?

—I guess they’d just spread out to fill the space of the box.

—Correct. Check it out:

—I follow you. In the end, they are many and easily reconfigurable.

—But now, imagine that instead of marbles we would have assembled different forms, interlocking them to fill the space of the box. Something like this:

—I see. If we had to transfer that structure back into a bowl it would be almost impossible. We would have to break it up and build a new one.

—Monolithic or tightly coupled structures don't adapt and eventually become obsolete. But adaptable structures evolve, adjusting to change after change.

—Very Darwinian, yes. But I can see something else.

—What?

—By facilitating the rearrangement, you enable higher order structures to emerge. In your example, suddenly you have round bowls, and square vases and many other types that, if they are themselves easy to combine, also could form higher order structures.

—Something like this?

—Yes! That would make the system not just adaptable, but emergent!

—Just like atoms forming molecules, cells creating tissues, or biological systems making up entire organisms. That’s why this whole idea got me thinking about how this pattern applies to people, teams, and organizations.

—How do you mean?

—Well, think about it—could the three principles of the Unix philosophy also apply to organizations?

—Hmmm… that's interesting.

—I went ahead and reworded the principles to fit organizations.

Take a look at the first one:

—It's a bit reductionist, but it's typically the case, isn't it?

—Yes, at least in theory.

—You mean that some teams don't do their job well?

—No… well, yes, that happens too, I suppose, but that's more a matter of competence. My point is that, if the principle is truly followed, two things should be clear:

—Hmm 🤔.

—Exactly. In reality, things aren't always so clear. Boundaries get blurred, responsibilities overlap — matricial structures, organizational silos, all that. And sometimes, things simply fall through the cracks — no one owns them.

—Yeah, we've all seen that happen.

— The first principle is really asking for just one thing: clarity. But in a large organization, clarity is easier said than done.

—Agreed. What about the second one?

—Check it out:

—This one’s pretty straightforward. In any organization of a certain size, if work is divided among different teams, then, by design, delivering that work requires collaboration between them.

—True, but it’s interesting how that idea has been challenged over the past few decades.

—How so?

—The division of labor has come to be seen as an outdated, industrial-era concept — something that only applies to repetitive, manual tasks. In contrast, knowledge work has shifted toward smaller, multidisciplinary teams that can adapt to changing and often unpredictable demands. The prevailing belief now is that the more autonomous a team is, the better. In fact, in some ways, we’re actively trying to reduce inter-team collaboration by giving each team as much independence as possible.

—But hold on a second, that logic has a flaw.

—Where?

—Would you say that a multidisciplinary team is a group of specialized individuals collaborating together?

—Yes, I do.

—Then, using your metaphor, isn’t a multidisciplinary team like a small set of marbles in a bowl?

—Yes, you are right.

—The same pattern you applied earlier at the inter-team level is now playing out within teams themselves. Instead of teams collaborating within an organization, we now expect individuals to collaborate within a team.

—True, but don't you find something interesting in that shift?

—What, exactly?

—The shift seems to acknowledge the challenge of getting large groups to collaborate effectively, especially under changing demands that require adaptation.

—True.

—Almost as if the Unix principles start breaking down at scale, and the only solution is to limit their application to a manageable group size.

—I see. Maybe it’s tied to some biological trait or an anthropological limit rooted in tribal behavior?

—Could be! I will look into that, but meanwhile, check the third principle, it will be revealing:

—Oh, dear! 🤦♂️ This is definetely a problem.

—It is! People’s interactions are anything but simple and efficient. Sure, they can be fulfilling and inspiring sometimes, but more often than not, they’re full of conflict and drama.

—Hell is other people.

—Yeah… well, I wouldn’t go that far, but you’re not wrong. It’s a real challenge. But think about it — when we looked at what made Unix such an adaptable and successful system, we were struck by this third condition, which I think is genius: having competent and specialized programs isn’t enough. They also need to work together smoothly, with minimal effort, almost seamlessly. That way, you get emergence — you step up a level and can tackle more complex problems.

—Sure, that's what we saw.

—It’s a pattern built into the very fabric of the universe. When we organize into groups, we’re trying to transcend our individual limitations. But then… interpersonal complexity gets in the way, making it rare for the third principle to be fully realized.

—Yeah, I think you are right.

—When I first read that third principle, it also struck me as oddly specific. The more I think about it, the more I realize it's the key to emergence, adaptability and evolution.

—So… is this a design flaw of Homo Sapiens?

—Hmmm, I'm not sure. If we assume that the functional objective of humans is to perpetuate the species, nature actually did a pretty good job designing an interface for that. You could say that API is well-defined, simple and — honestly — pretty seamless.

—Eeeeh… 🙄 ok, that’s an interesting way to look at it.

—The real question is how well-equipped humans are to pursue any goal other than that.

—I see.

—Google conducted a study to identify the key factors behind high-performing teams. By running statistical models across their organization, they discovered five key dynamics that drive team success. It’s interesting to look at them through the lens of our principles.

—Some of those dynamics are closely connected to our principles! Take point three, Structure & Clarity—it’s clearly linked to the first principle: everyone knows their responsibilities.

—They all are! Psychological Safety and Dependability relate to how effectively team members interact, don’t they? A team that embodies these traits will speak up when necessary and handle dependencies constructively.

—Agreed. And what about Meaning and Impact?

—Those suggest that team members don’t just share a goal on paper—they genuinely believe in it. Remember the API for procreation?

—How could I forget?

—We talked about how the real question is whether we can jointly pursue any other goal. I think this ties in—statistically proving that when team members deeply believe in a common goal, their interactions flow effortlessly.

—That makes total sense.

—See? Most of these ideas connect back to principle three. The interface needs to be simple, effective, almost inevitable.

—Yes, I see it now. Initially, principle three seemed trivial and overly specific, but its significance is becoming clear.

—Exactly. And when you look at it from this angle, there’s something worth noting.

—What is it?

—The biggest constraint that prevents teams—or any larger group of people—from evolving into adaptable, creative, and emergent organizations isn’t the quality of their members or how they are organized, but how they interact, communicate, resolve conflicts, and make decisions.

—Here's an important takeaway:

—Yeah, if I follow your reasoning, that makes sense. But it’s wild how much time gets spent defining areas and departments, yet so little goes into analyzing how they interact and how those interactions should actually work.

—Et voilà!

—But all this ties directly into the concept of Collective Intelligence!

—Exactly. And I think the real key to unlocking Collective Intelligence is figuring out the Human Interface—how to get people to collaborate as effortlessly as atoms bonding to form molecules.

—That’s a fascinating idea—unlocking a higher level of evolution by optimizing human interactions… wow.

But I’m not sure it’s even possible. There are so many challenges…

—I believe we can help you with that.

—Wait a moment! What exactly do you mean by 'we'?

—We, the AI.